Strandings Overview for 2023

In September 2023, the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) requested that IWDG include sea turtles as part of its remit. Although IWDG regularly logs sea turtle strandings in our database, volunteers were not previously asked to attend these events to collect additional data. We have now developed a sea turtle data collection protocol to send to our Stranding Network volunteers.

The IWDG Stranding Scheme identified a decrease of 31.6% in stranding records in 2022 (n=268) when compared to 2021 (n=392) – which were the highest numbers in a calendar year on record. This decrease has not continued into 2023 as the number of strandings have increased by 32.5% (n=355) from 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Total number of validated stranding records reported to the IWDG between 1990 and 2023.

During 2023, the IWDG were able to identify 85% of animals reported to species level (n=302), with a total of fifteen species identified (Figure 2). This higher number was due to several rarer species washing up, such as the northern bottlenose whale, True’s beaked whale, and humpback whale. The number of species recorded by the scheme was slightly lower in previous years; 2020 (n=12), 2019 (n=13), 2018 (n=12) and 2017 (n=13).

Figure 2. Total cetacean stranding records by species in 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2023

Two mass stranding events involving animals which eventually died were reported in 2023, down from three in 2022, and six in 2021. This is significantly down compared to 2020 during which there were 12 events reported. Mass stranding events in 2023 involved only one species – the common dolphin. The events consisted of one group of two and one group of ten.

Common dolphin

Common dolphin strandings in 2023 were up by 26.4% (n=172) compared to 2022 (n=136), representing 48% of all stranding records. Stranding numbers for this species continue to remain greatly elevated since 2011. Overall increase in stranding records could be due to a multitude of factors, such as i) increased awareness of IWDG via social media ii) ease of reporting now possible with the IWDG Reporting App iii) increasing abundance or a change in distribution iv) anthropogenic interactions.

Harbour porpoise

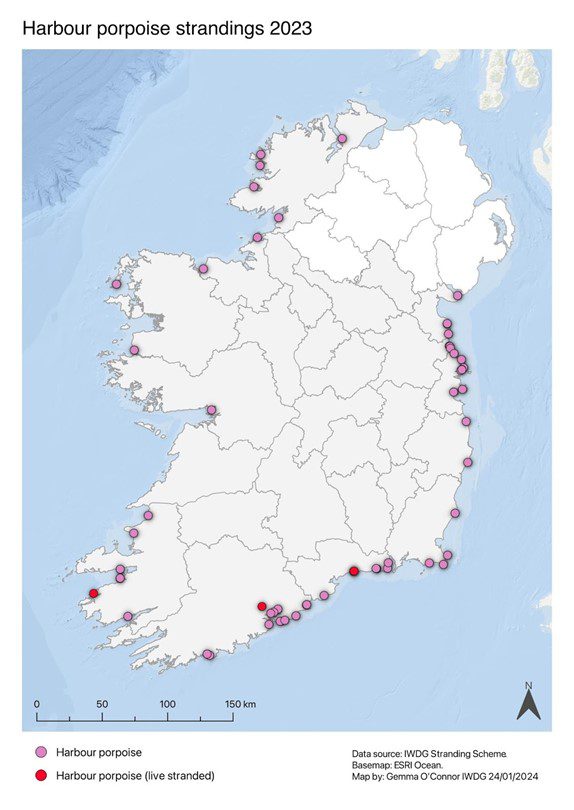

As in previous years, the harbour porpoise was the second most frequently reported species representing 18% (n=63) of all strandings, up from 15% (n=41) in 2022. The year 2023 represented a new stranding peak for this species, with the previous peak consisting of 48 animals back in 2020. As with common dolphins, harbour porpoise strandings have shown an upward trend starting in 2011. The majority of harbour porpoise strandings occurred along with east/southeast coasts in 2023 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Location of harbour porpoise strandings reported to IWDG in 2023.

Northern bottlenose dolphins

Three whales were reported stranded in 2023, one in Co. Down in August, and two in County Cork during the month of November – one of which was live stranded in Allihies, though it died shortly after (Figure 4), and the second animal was reported the following day in Glengarriff, Bantry Bay. A post mortem examination was carried out on the live stranded animal under DDRIP.

Figure 4. Northern bottlenose whale live stranded in Allihies, Co. Cork on 12 Novembers 2023. Photo Charlie O’Connor.

These strandings followed an unusual string of sightings of a group of three northern bottlenose whales in Bantry Bay which were reported in the Inner Bay between the Ballylickey inlet and the back of Garnish Island.

Striped dolphins

In 2023, 17 animals were recorded stranded, making it the second highest year on record for this species after 2014 (n=18). Of the 17 animals reported, six were observed to be live stranded, while one was a suspected live stranding. Fourteen of the 17 animals reported were classed as being ‘fresh’ or ‘very fresh’, it is therefore likely that some of these animals may have also died as a result of live stranding.

Minke whale

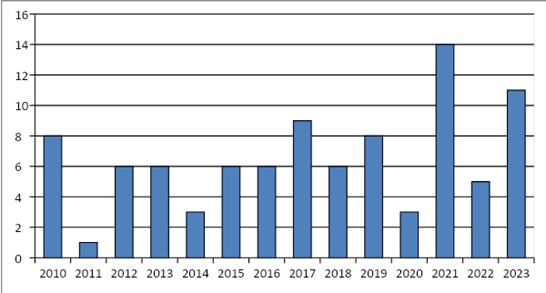

Numbers were up in 2023 for the minke whale with 11 animals reported, making it the second highest year on record for this species (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Total number of minke whale strandings reported to the IWDG from 2010 to 2023

Of the seven animals that were visited by a volunteer on the IWDG Stranding Network, three were inaccessible due to the location of stranding. Of the remaining accessible animals, two were identified as being possible entanglement cases, one probable (Figure 6), and one definite as the animal was seen entangled in fishing gear at sea.

Figure 6. Male minke whale with rope marks in Slade Harbour on 3 May 2023. Photo by Jim Hurley.

Discussion

Due to the overall increase in stranding numbers year on year, particularly among common dolphins and harbour porpoises, the IWDG continues to stress that action is required as soon as possible to identify the cause(s) of these strandings. Only then can we identify possible solutions from both a welfare and conservation perspective.

There are many factors which may influence stranding rates. Prevailing winds can influence whether a carcass makes landfall, whereby predominantly easterly winds may reduce the number of animals washed up on the west coast. Factors such as the distribution of fishing effort and the distribution of dolphins, both of which are influenced by the distribution and abundance of fish, may also influence stranding as well as mortality rates. A shift of cetacean populations to more coastal waters could possibly be occurring, as sightings records from the IWDG Sighting Scheme were the highest ever on record in 2021. More critical analyses of the stranding database, including exploring some of these confounding factors, is required.

IWDG has attended several meetings with stranding scheme managers from neighbouring countries (France, UK, Spain, Portugal), whose post mortem schemes allow them to demonstrate that bycatch is the most common cause of death for common dolphins. Becoming entangled in fishing gear was the primary cause of death found in common dolphins during the winter period in France according to researchers at the Pelagis Sea Mammal and Bird Observatory, after a record number of dolphins (n=370) were reported along the Bay of Biscay between 1 December 2022 and 25 January 2023. When comparing trends from the IWDG Stranding Scheme with schemes from neighboring countries they are quite similar, suggesting similar pressures are applying to a much wider area than just Ireland.

Also in France, a 2020 study used drift modeling to identify where common dolphins presenting with signs of bycatch had initially died. In doing so, the study was able to identify potential fishing fleets which may have been involved in the stranding event, and therefore recommended further investigation into these fisheries (Peltier et al 2020). Carrying out a similar study in Ireland using drift modeling to locate the likely point of mortality is recommended, with the results more useful if only animals that had died from bycatch were used. In order to understand the drivers behind the increase in stranding rates, the IWDG requires evidence to report on and inform government and industry. Photographs taken from IWDG volunteers have shown many animals, in particular common dolphins and harbour porpoises, in poor nutritional condition (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Juvenile harbour porpoise in poor nutritional condition reported from Laytown Beach, Co. Louth on 18 September 2023. Photo by Orla Tuthill.

Infectious diseases and malnourishment were responsible for a high proportion of deaths during the 2017-2019 post mortem scheme, which may be linked to this increased presence in inshore waters as animals have to travel further afield to obtain their daily nutritional requirements.

It is interesting to note that the IWDG have identified significant declines in harbour porpoise densities in all three Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) designated to protect this species (Roaringwater Bay and Islands, Blasket Islands and Rockabill to Dalkey Islands). Results from boat-based surveys carried out on behalf of the NPWS suggest that this may not be the result of population declines, but rather changes occurring in their distribution – changes which are likely driven by shifts in the distribution of their preferred prey. In addition, recent ObSERVE aerial surveys (2022-2023) have also noted a lack of harbour porpoise sightings (M. Jessopp pers. comm). It is too early to correlate these two separate signals, but poor nutritional states in our harbour porpoises caused by changes in prey distributions could potentially lead to increased stranding rates.

Many mariners, including fishers, are commenting to the IWDG that they never used to see so many dolphins when they were at sea years ago. This perception is widespread and has merit. There is evidence of an increase in common dolphin abundance in inshore waters to the south of Ireland in the Bay of Biscay (Astarloa et al. 2021), which has been associated with changes in climate indices and prey. If a similar increase has occurred further north off Ireland, this may in some part explain increased stranding rates, as increased numbers inshore will inevitably lead to an increase in strandings.

As top predators, cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) have long been identified as important indicators of ocean health, and have been suggested as a tool for monitoring the changing conditions of the oceans and to inform government policies. A recent publication recommended using long term stranding scheme data as a tool for informing climate change policy in the UK (Williamson et al. 2021). Researchers examined data from the UK’s Cetacean Stranding Investigation Programme (CSIP) and reported an increase in warm water adapted species (common and striped dolphins), and a decrease in cold water adapted species (white-beaked and Atlantic white-sided dolphins). The IWDG are seeing a similar trend with regards to the common and Atlantic white-sided dolphins. Common dolphin strandings in Ireland have been increasing significantly over time, however, the number of stranded Atlantic white-sided dolphins has been decreasing since 2012. These trends are consistent with records reported to the IWDG Cetacean Sighting Scheme.

Williamson et al. (2021) identify one of the main drivers of this change to be shifts in the abundance and distribution of prey due to climate change, and refer to documented cases of this occurring in the North Sea, the Irish Sea, and the wider N. Atlantic.

Research

Data from the IWDG Stranding Scheme have been used in many studies over the years. More recent work using samples from the Irish Cetacean Genetic Tissue Bank (ICGTB) aimed to investigate population structure, genetic diversity, and individual relatedness among the Atlantic white-sided dolphins in the North Atlantic. Results indicated that there is no difference in the genetic diversity of Atlantic white-sided dolphins across the North Atlantic, suggesting this species needs to be managed as a single population (Gose et al. 2023).

Another study assessed the impacts of anthropogenic activities and environmental change on the foraging ecology and nutritional status of common dolphins, and identified a significant decline in their nutritional condition when comparing data from recent years to historical records (S. Albrecht, pers. comm).

Northern Ireland

A total of 19 strandings were recorded from Northern Ireland which consisted of three species : common dolphin (n=8), harbour porpoise (n=7), and one northern bottlenose whale. There were two animals classed as ‘common or striped’, and one classed as ‘cetacean species’.

Stephanie Levesque – IWDG Strandings Officer