The most common baleen whale in the world and the one most commonly harpooned by whalers is the one to which we have given the least attention. Because we seem to think anything we do cannot impact minke numbers, which of course is not true. Apart from whaling minke whales face an increasing threat from fishing, entanglement, vessel strike and climate change but one of the principal impacts can be noise. The impact of noise must be measured against the hearing ability of these whales but also vocal range used. It is important that vocalisations which the whales use in the opaque environment underwater are not masked or covered up, to allow mating and reproduction as well as feeding and important social interactions to continue as it has for millennia.

The importance or otherwise of Irish waters for the North Atlantic minke population remains unknown and the exact purpose of minke vocalisation can be guessed at but is not known. Where minke whales go to in Spring and Autumn remains unknown but there are few in Irish inshore waters in winter. I have noticed for the last number of years two peaks in numbers, one in spring, typically in April off the Beara Peninsula and another in July or August and these correspond to an increase in numbers generally off West Cork and Kerry. Given the belief that minke whales calve in the December to February period and are thought to have a 10 month gestation period then any vocalisations associated with mating activity should more likely occur in the period February to April. Given that we often see numbers of minke whales in April off Beara this seemed to be a logical month to try and capture some minke whale acoustics. The most distinctive vocalisation that are attributed to minke whales are what we call pulse trains which most people describe as resembling a fast heartbeat.

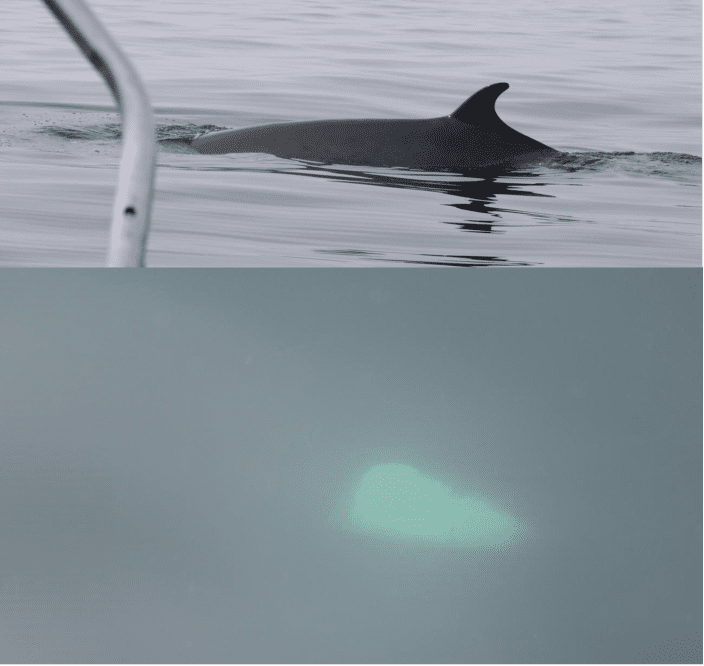

In April 29 2021 with a loan of a drop down hydrophone from Thomas Gordon and with a small RIB courtesy of Ruairí O’Sullivan we managed to get out into a loose feeding aggregation of common dolphins and minke whales . It was my first time using this simple hydrophone setup and I put the hydrophone in the water and put it on record and by the time I got the headphones on (less than two minutes) I had a very clear thump train already, that was clearly audible but this minke whale (figure 1) also produced clicks associated with the pulses. The purpose of the clicks remains a mystery and is not present on all pulse trains. It is assumed pulse trains are only produced by males and such vocalisations are rare in the North Sea where many minke occur.

Figure1 Minke passes under the RIB April 30, 2021, following pulse train

While it remains to be determined that pulse trains are associated with mating activity this does seem probable. However it is important to understand how widespread this vocal activity is along the Irish coast. The Observer acoustic program in 2014 and 2015 only recorded some pulse trains off Donegal in Spring and Autumn. But with approximately 6.5 hours of good recordings off Beara from drifting hydrophones numerous pulse trains were obtained along with various other vocalisations which are believed to be that of minke whales though this remains to be definitely established.

Figure 2 Minke whale under and near the RIB April 29th, 2022, shortly after pulse train.

This pulse train was from a minke whale in Figure 2 which remained under the RIB for some seconds. Beara Peninsula in on April 29th.

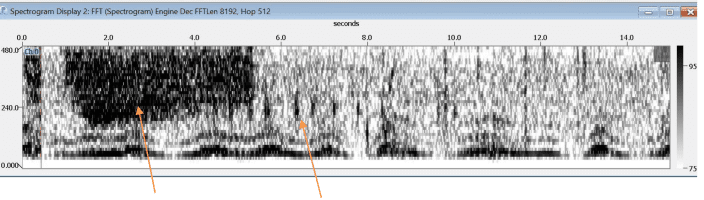

The vocal activity occurs in the frequency range of 150 Hz to 350 Hz principally and this is the range most impacted by ship noise and pile driving and establishment of vocal habits prior to offshore works may be of critical importance to maintaining a healthy minke whale population. The interference of vessel noise in the immediate vicinity of minke whales is visible on the spectrogram in figure 3. It is believed that pulse trains are detectable over relatively short distances of 2 to 10km but there are other acoustics that are produced which appear weaker, and the clicks detected twice in 2021 have not been detected since. Minke whales appear to transit both sides of the Irish coast, through the Irish Sea and off the West coast up to Scotland but this assumption remains to be tested. Whether mating vocal behaviour continues during this movement remains to be seen. We have seen once prolific species reduced to a handful in many parts of the world by careless development, therefore it is important to properly understand the environment before we seek to develop.

Figure 3 Masking by fishing vessel of short minke pulse train May 2nd 15.51 hrs

To date West Cork is the only location in the North East Atlantic where minke whales have been seen to frequently vocalise. This begins to suggest that this area may be important from a conservation point of view specifically for minke whales but there is no evidence to suggest more areas along the Irish coast are more, less or equally important. Keeping low frequency interference to a minimum will help to keep a healthy minke whale population. Knowing where minke vocalisations occur and suspension of development activity during key periods may be required to prevent industry noise interfering with important mating activity periods. This highlights the necessity of comprehensive acoustic baseline data for all industrial developments offshore to understand the vocalisation behaviours of minke whales and the ambient or background noise in which they live. Until the start of the 20th century much shipping traffic was under sail and consequently much quieter, there were no offshore oilfields and windfarms and no sonar used. Since the middle of the 20th century noise intensity in the oceans has risen 3dB on average per decade. This represents a doubling of noise intensity every decade. It is time we looked at the impacts we have on the marine environment properly and there is much we can now do to reduce these impacts.

The final report on ‘Minke vocalisations in Irish waters’ by Patrick Lyne will be published soon.

Author: Patrick Lyne, IWDG Officer and Marine scientist