The Shannon Dolphin Project has been running for 30 years, barely three dolphin generations. However. we have gained some knowledge on their movements and use of the estuary, identified important foraging areas, documented calving rates, adult and calf survival and understand a little about their social structure. This work has shown the estuary is a very important habitat for a relatively small, genetically discrete and largely resident population. These are important parameters to determine the long-term prospects for the Shannon Dolphins and to provide baselines against which to measure change.

But what happens next. What is the future of the dolphins and the project ? Has it run its course? Do we try and continue for another 30 years, building our knowledge? sharing out stories? or is their a new era for the Shannon Dolphin Project ?

Interest was largely local

For the first 28 years, there was little or no funding for long-term monitoring and most interest in the dolphins was local. They supported dolphin-watching, which became commercially important in the ports of Carrigaholt and Kilrush. Small scale research projects were undertaken, third-level students supported. On a county wide basis, Clare County Council used the dolphins as the logo for their litter campaign. School visits, largely funded by the Heritage Council, introduced children to the dolphins and their unique Shannon Estuary habitat.

In 2000, the estuary was designated as a European Marine Protected Area for bottlenose dolphins in which was very important. This led to ongoing population monitoring funded by the NPWS as part of their reporting obligations to the EU. However there is still no Conservation Management Plan for the estuary or the dolphins, so users don’t really know what is being protected, what are the pressures and how are these going to be managed. The MPA designation has however contributed to the conservation of the dolphins, but only because the IWDG, through the Shannon Dolphin Project, has been representing their interests and advocating for them.

What changes have we seen over the last 30 years?

One of the main drivers of the Shannon Dolphin Project at the beginning was to explore the feasibility of dolphin-watching in the estuary. 30 years later there is little dolphin-watching, no trips available from Carrigaholt and Dolphin Discovery in Kilrush in its last year of operation. This is not due to the lack of dolphins, but more the lack in investment and promotion of the dolphins as one of west Clare’s unique selling points: a resident population of dolphins. Marine wildlife tourism is expanding in other parts of Ireland but it seems to have dropped off in the Shannon. These things come in cycles and a new operator is planning to work out of Carrigaholt and no doubt new opportunities will emerge in Kilrush.

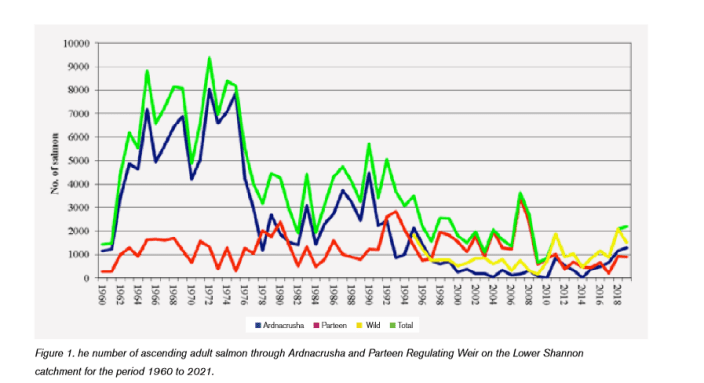

Irish Whale and Dolphin Group research over the last 30 years suggests some of the dolphins in the outer estuary may be spending less time in the estuary than previously documented. This is most likely due to the lack of their preferred food, requiring the dolphins to hunt further afield. Despite a ban on salmon fishing in the estuary in 2007, salmon numbers have failed to recover in the Rivers Maigue, Mulkear and Fergus. Salmon are an important food source for the Shannon dolphins and healthy fish stocks are important for all interested parties. Long terms changes in fish distribution are inevitable with the impacts of warming sea temperatures driven by climate change. Dolphins are adaptable and have the potential to switch if preferred prey becomes less available.

We have been explored the potential effects of persistent pollutants[1], mitigated dredging at ports and harbours and monitored disturbance from dolphin-watching vessels. None of these have had major impacts on the dolphins, but were worth considering and monitoring. We have been concerned with the removal of hundreds of tonnes of important forage fish, such as sprat, which must have a negative effect. The IWDG have been calling for a moratorium until we understand the role of sprat, and other pelagic fish, in the dolphins diet. The Lower River Shannon is an MPA and controls on fishing must be part of a management regime if there are real concerns.

New pressures on the estuary

For the first 28 years of the Shannon Dolphin Project their were very few major new pressures on the estuary. However progress towards the planned economic development of the Shannon Estuary is advancing fast. The estuary has always been a busy waterway due to its deep-water berths which facilitates large vessels able to discharge in bulk. This has led to the development of large power stations at Moneypoint and Tarbert, an alumina smelting plant at Aughinish, an airport at Shannon and a bulk cargo facility at Foynes Port.

Despite plenty of aspirations, little has changed in the Shannon Estuary over the last few decades, but this is all due to change. The estuary is braced for a huge increase in development; the transition of Moneypoint Power Station to a green energy hub supporting offshore renewables, the expansion of Foynes Port and the proposed Shannon Technological and Energy Park at Ardmore Point, including an LNG terminal.

One of our major concerns has been the potential impact of increased noise levels in the estuary. Dolphins live in an acoustic environment and any loud, mid-frequency sounds can lead to masking and reduce their ability to communicate and hunt.

Proposed developments will inevitably increase traffic in the estuary. How can we prevent increase noise pollution, both during construction and operation? New vessels are typically quieter, but increased activity will inevitably lead to a cumulative increase in noise. The IWDG have been proposing a noise threshold in the estuary, below that known to impact negatively on dolphins, be set and noise levels monitored. However we need to create a noise map now to use as a reference with which to monitor changes.

Transition to electric powered vessels could reduce cumulative noise over the long term. Electrifying the Shannon ferry, which has been shown to be an important source of noise pollution[2] is very achievable. It plies a regularly, predictable route with its home port only a few kms from the newly announced Green Atlantic Hub at Moneypoint which will receive renewable energy from a suite of offshore wind farms.

Another source of ocean noise in the estuary which is increasing, are large ships on anchor. These vessels run generators while on anchor and these produce not insignificant amounts of above water noise. The levels of underwater noise from these vessels has not been quantified. As part of their green port strategy the Port of Aberdeen have provided offshore moorings with power banks to which ships can plug into, accessing renewable electricity generated during periods of high wind, enabling them to turn off generators and reduce noise emissions while on anchor. This innovative idea, amongst others, could work very well in the Shannon Estuary to reduce cumulative noise emissions.

All-Estuary Approach to monitoring

Since 2020 the IWDG have been funded to roll out a suite of acoustic, boat and land-based monitoring to inform environmental impact assessments in the estuary. For the first time the Shannon Dolphin Project is being supported financially as there is a real interest in the dolphins, which are seen as a potential threat to these developments. They are, and these threats are not going away but will build if they continue to be ignored. As well as support for the project the IWDG are able to discuss directly with the developers our concerns and identify mitigation measures.

The IWDG have always advocated an All-Estuary monitoring approach with a long-term (at least 10 years) vision and associated conservation objectives. Integrated monitoring should include bottlenose dolphins, seabirds (breeding and feeding) and key fish species in the estuary. We need to include triggers which solicit a management response before impacts become too significant. Decision makers and managers must embrace their conservation obligations, build an evidence base, monitor the effects of activities and establish a mechanism for feedback to all interested parties, through adaptive management structures to ensure economic development can only progress with no significant impacts on the estuary and its inhabitants.

A healthy dolphin population reflects well on the quality of the estuary. Dolphins are top predators and by minding and monitoring them we will look after the estuary as a whole. Is this the opportunity to mainstream the Shannon Dolphin Project; align it with economic development to ensure the dolphins and their habitats are protected? Monitor pressures, flag emerging issues, bring results and trends to the attention of an All-Estuary Environmental Monitoring Committee ? or continue to lie on the fringes and maybe monitor the slow demise of the Shannon Dolphin Population ?

Will there be dolphins in the Shannon estuary in 30 years’ time?

We hope so.

Dr Simon Berrow

[1] Berrow, S.D., McHugh, B., Glynn, D., McGovern, E., Parsons, K. Baird, R.W. and Hooker, S.K. (2002) Organochlorine concentrations in resident bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the Shannon Estuary, Ireland. Marine Pollution Bulletin 44, 1296-1313.

[2] O’Brien, J.M., Beck, S., Berrow, S.D., André, M., van der Schaar, M., O’Connor, I., and McKeown, E.P. (2015) The Use of Deep Water Berths and the Effect of Noise on Bottlenose Dolphins in the Shannon Estuary cSAC. The Effects of Noise on Aquatic Life II. Volume 875 of the series Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology pp 775-783.

For those interested in learning more about the Shannon Dolphin Project and shaping its future please join us in Limerick on Wednesday 4 October at the Shannon Dolphin Seminar

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/shannon-dolphin-seminar-tickets-675168877287?aff=ebdssbeac&keep_tld=1