Role of the IWDG in Live Strandings

IWDG are a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) who aim to promote better understanding of cetaceans and their habitats through education and research. We do this by the collection and distribution of data and collaboration with universities, government and research groups. We operate a stranding scheme which records the incidents of dead or live cetaceans around the coast and maintain a stranding network made up of trained IWDG members.

When a live stranding occurs, IWDG are often the first port of call and we will always do what we can to assist and to advise the best course of action to take for the welfare of the cetacean(s). However, as we are an NGO it is important to note that we are not the official competent authority tasked with responding to stranding events. Currently in the Republic of Ireland, there is no authority who has taken on this role. So in the absence of an official competent authority, the IWDG as an NGO act to assist live-stranded animals, whether it is basic first aid, providing palliative care or refloating if deemed appropriate. In Northern Ireland, the competent authority is the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA). The equivalent in the Republic would be the National Parks and Wildlife Services (NPWS) but they have not yet accepted this role. We would like to see this role taken on officially, and to work in an advisory capacity in order to provide expert advice and assistance. IWDGs officers and members are extremely dedicated and experienced, but most work with us on a voluntary basis and have full time jobs outside of the group. Unless something changes at a higher policy level, and an official framework and set of protocols is adopted regarding live strandings, the status quo will not change.

What is a live strandings and why do they occur?

A live stranding is a living animal that comes ashore and is unable to return to the sea, occurring in two forms: single strandings and mass strandings. Some causes of live strandings may be due to natural reasons and outside our control, while other causes can be greatly reduced or even eliminated through human actions. The following are a list of causes which may contribute to the incidence of live strandings of cetaceans in Ireland; health and old age, group cohesion and family bonds, navigation error, environmental factors, foraging and anthropogenic causes (human activity).

Strandings, and in particular live strandings, can be distressing for many people. To see cetaceans out of their natural habitat and in distress is upsetting and our immediate reaction is to try and help in whatever way we can. However, it is important to first assess the situation and to ensure that any action taken is in the best interests of the cetacean, which may not always be the easiest course of action for yourself. While every stranding is different, the welfare of the cetacean must be the highest priority.

What can we do on the scene of a stranding?

First and foremost it is important not to panic, and to rationally assess the situation. Cetaceans are mammals meaning that they are warm blooded, air breathing, and can survive out of water for some time as long as certain basic needs are met.

If possible, a veterinary surgeon, marine biologist or someone with experience of live-stranded cetaceans should be asked to attend the scene as soon as possible to determine the health of the animal.

If the animal is alive, try to keep it wet and cool. This can be done by placing wet towels, seaweed or other material over it or gently using buckets of seawater, but it is vital to ensure the blowhole is kept clear.

If it is sunny try to provide it with shade, as cetaceans can get sunburnt!

Turn the animal on to its stomach if it is possible to safely do so, taking care not to damage the flippers by pushing or pulling on them. If the animal is on a sandy or soft surface, it is advisable to dig some space underneath its pectoral fins if possible. This will alleviate some of the pressure on the fins caused by its body weight.

Never attempt to drag the animal, especially by the tail as this can cause severe injury and stress.

Care should be taken to use gloves and to practice good hand hygiene. Some cetaceans may carry zoonoses which are diseases or infections transmissible from animals to humans.

It may be necessary to call for assistance with crowd control from An Garda Síochána or the Coastguard

At all times it is important to keep noise to a minimum, dogs under control and to move as quietly and respectfully as possible while providing care to the animal. We have to remember we are dealing with a wild animal which is not used to close human contact and totally helpless in an alien environment. Every effort should be made to make it as comfortable as possible and to reduce additional stress.

Welfare of the animal(s)

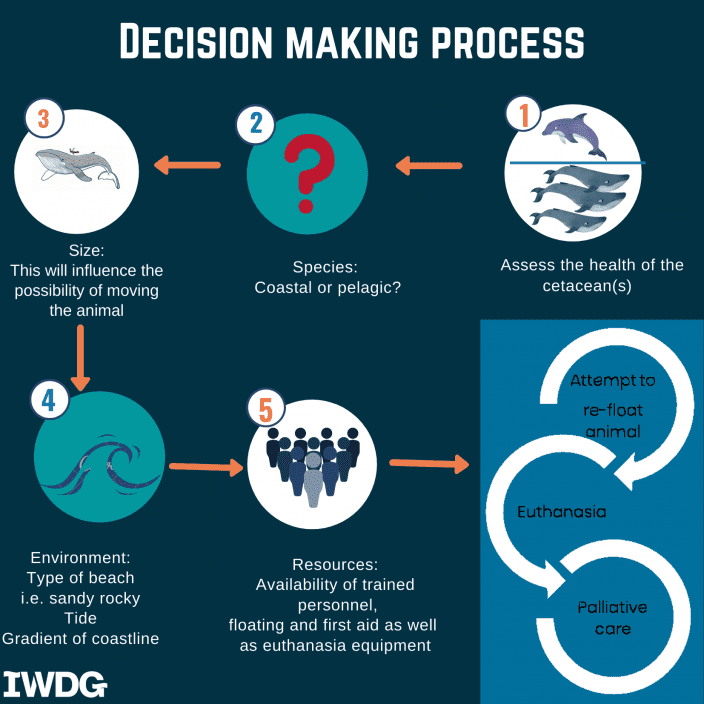

At this point the health of the cetacean must be assessed ideally by a veterinary surgeon, a marine biologist or someone experienced with live-stranded cetaceans. This can be difficult but may be done by examining the following: nutritional state (i.e. is it emaciated or in poor body condition), temperature, breathing rate, and presence of severe injuries. While undeniably unpleasant for the animal, flesh wounds and abrasions are not always critical and could have been caused during the stranding event itself, so are not always an indicator of poor health. Evidence of acoustic trauma can not always be seen externally and often may only be determined during an extensive necropsy.

There are three options to subsequently consider; attempt to return the animal to the sea with a refloat, euthanasia, or allow it to die naturally.

However, ultimately the main thing to consider is the state and health of the stranded animal and to determine what action is in their best interests.

Refloating

While the natural and empathetic reaction is always to jump in and to attempt a refloat, it has to be considered whether or not taking this sort of action is in the best interests and welfare of the animal(s). Attempting a refloat so we can feel like we have at least ‘done something’ makes it more about us than animal welfare. So a refloat should only be attempted when all of the above factors have been considered and it is deemed in the best interest of the animal. On some occasions, a refloating attempt is the best course of action if the animal(s) are healthy and human safety is not put at risk. There have been a number of successful refloating attempts in the past, particularly on the north-west coast of Ireland with groups of live stranded dolphins. However, an animal which is sick or injured is not going to benefit from a refloating attempt, in fact any such attempt may prolong its suffering. The physical maneuvering of the animal may cause additional pain and injury as well as the increased stress of being in close proximity to humans and being handled.

It has to be remembered that cetaceans are highly sentient and intelligent beings. Any cetacean which live strands may have a reason for doing so in the first place, such as natural causes. There are also occasions where cetaceans strand due to navigation error or where they find themselves in an environment that they cannot navigate out of such as slowly shelving coastline or changing sandbanks. This may be relevant to offshore deep diving species who are suspected to have been exposed to acoustic trauma.

Euthanasia

Euthanasia has been defined as ‘the use of humane techniques to induce the most rapid and painless and distress-free death possible’ (AVMA, 2013). While it is often suggested when dealing with a live stranding with a bleak outcome, it is one of the most challenging tasks to undertake. Considerations include the welfare of the animal, personal safety and eco-toxicological hazards as well as the availability of appropriately trained and licensed individuals (Barco et al., 2016). In Ireland, this field has not been sufficiently developed yet. At present euthanasia by drugs or by shooting are the two options and have only been carried out to a limited degree. Shooting has not been used on a large animal in Ireland to date, with most incidences of euthanasia carried out on small dolphins using drug methods and the largest animal being a sei whale live stranded in Larne Lough in 2013. Ballistic methods such as shooting or explosives would have to be carried out by appropriately trained and licensed individuals in order to ensure human safety and the most humane death possible for the animal.

Human safety interests must always be considered as cetaceans are powerful animals even when severely debilitated. While not generally aggressive towards humans, a dying or injured animal may thrash around violently and potentially cause serious harm to a well-meaning onlooker or veterinary surgeon.

An animal which has been euthanized represents a biological hazard due to the toxic chemicals introduced into the body (Bischoff et al., 2011). The disposal of the carcass needs to be carefully handled and often incineration is necessary, a task which may be outside the scope of our local authorities especially when dealing with a large animal. A commitment is needed from governmental agencies in order to develop effective and approved procedures for euthanasia where appropriate, and this is something that the IWDG have been pushing for. In the absence of this, there is little that the IWDG as an NGO can do to advance and further euthanasia methods to provide more options in the event of a live stranding other than allowing a natural death.

Natural Death

If a refloat is not deemed appropriate and euthanasia is not possible, the last remaining option is to allow the animal to die naturally and to keep it as comfortable as possible in the process. In the public eye this remaining option is not always a popular one and can cause conflict and uproar. Yet if an animal is in poor health and it is not possible to refloat or carry out euthanasia, sometimes the kindest thing that can be done for a live-stranded animal is to provide palliative care and give it peace and respect to die in dignity. As counter intuitive as this may seem.

While we have sufficient cause to believe that certain strandings (particularly mass strandings) may be as a result of anthropogenic activities. It is important to remember that like any other animal population, individuals will routinely die due to natural causes such as old age, illness or disease. However, as cetaceans live in an open water environment, we do not always see the results of this natural process. Other environmental factors such as tides, wind direction and swell may influence whether a dead or sick animal drifts ashore where it may strand or if it is washed further out to sea. Just because an animal has stranded or beached itself does not mean that it can be saved, or that humans may be to blame. We may just be seeing a natural process.

Meadhbh Quinn

IWDG Officer

References

American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) (2013) AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2013 Edition. American Veterinary Medical Association 1931 N. Meacham Road Schaumburg, IL 60173 ISBN 978-1-882691-21-0.

Barco, S.G., W.G. Walton, C.A. Harms, R.H. George, L.R. D’Eri, and W.M. Swingle. 2016. Collaborative Development of Recommendations for Euthanasia of Stranded Cetaceans. U.S. Dept. of Commer., NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OPR-56, 83 pp

Bischoff, K., Jaeger, R., & Ebel, J. G. (2011). An unusual case of relay pentobarbital toxicosis in a dog. Journal of medical toxicology : official journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology, 7(3), 236–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-011-0160-8